If God exists, then why is He so shy? Why doesn’t He reveal Himself in more ‘obvious’ ways? Those questions form the basis of an argument against the existence of God that has been gaining a lot of attention in recent years, the argument from “divine hiddenness”. As a former atheist, I can relate to the argument; it’s a tough question. I remember many years ago riding in a car with a friend and we came across a billboard that depicted a blue sky and some pretty white clouds and it read: “Looking for God?” At the bottom, it advertised going to a local church to ‘get answers.’ I laughed and I said to my friend “yeah, I looked for God, but I sure as hell didn’t find Him!” I joked that the blue sky and clouds represented what God really was; nothing but empty space. Seeking God was like seeking a passing cloud; pointless.

The crux of the argument from “divine hiddenness” is this: What kind of God would let well-meaning, intelligent people who seek good evidence of the divine in the midst of this suffering world fail to find it? Why does the seeker come up empty? Why are their efforts frustrated? Not only have I dealt with this objection myself, I’ve also come across many people who have had the same problem. They seek after God and they find nothing. They ask for a sign and no sign comes. They ask for something in prayer and the prayer goes unanswered. It really makes you think no one is there, that no one is listening, right?

But what if I told you that the problem lies not with our intention, but with our orientation? The great Sufi mystic Bayazid Bistami once said “for thirty years I sought God. But when I looked carefully I found that in reality God was the seeker and I the sought.” Put simply, our God is the Seeking God. To be able to truly seek God, we must first realize that He is seeking us.

We learn that God was seeking us right from the beginning, all the way back in Genesis. You probably know the story. They ate the forbidden fruit, they became aware of their nakedness and they hastily sewed clothes together from fig leaves to hide their shame from one another. And then they try to hide from God Himself. And yet, God is not content to let them hide. He comes down and He seeks them out. Despite the fact that He knows full well where they are, He asks “where are you?” The Seeking God forces them to acknowledge their hiddenness. It is not God who hides from us; it is we who hide from God.That moment in the Garden is the pattern for all of human history. Thus, it is our orientation from the very beginning to seek to hide ourselves from the presence of God. Isaiah 59:2 echoes this in saying: “Rather, your iniquities have been barriers between you and your God, and your sins have hidden his face from you.”

The theme of the Seeking God continues throughout the entire Old Testament. We see how God communicates with His people, even when they aren’t trying to seek Him. He reaches out to people caught up in the midst of their daily routines or in the dead of night. He interrupts them. He comes to Abram in the middle of the night and tells him to pack all His things, take His family and go to a land “that I will show you.” After his stint in Egypt, Moses was seemingly content living out his retirement as a shepherd when God suddenly appears to him in the Burning Bush and calls him to be the liberator of the Hebrew people. In the story of Jonah, God calls him to be a prophet to the people of Nineveh, but he runs away. God then pursues Jonah relentlessly until he finally comes to terms with God’s plan. These stories serve to remind us that it is God who takes the initiative.

This pattern of the Seeking God culminates in Jesus Christ; when through the Incarnation God Himself comes down to visit His people. The theologian George Eldon Ladd wrote “In Jesus, God has taken the initiative to seek out the sinner, to bring the lost into the blessing of His reign.” We may try to hide from God, we may try to run from God, but He comes to us, and He comes to us out of love. In the words of Jesus Himself, “For the Son of man came to seek and to save that which was lost.” (Luke 19:10)

I would encourage any of my readers who are curious about this concept and would like to explore it in more detail to please read the Gospel of Luke Chapter 15. Jesus was facing harsh criticism from the religious leaders of His day for ministering to sinners and even being in their presence. The great truth of the Seeking God is laid out in three Parables that Jesus taught. He said that it was His divine purpose to search out the sheep that had strayed; to seek the coin that had been lost, and to welcome the prodigal back into the family even though he was unworthy of forgiveness. It is God’s initiative every time. The shepherd searches for the lost sheep; the woman sweeps the house looking for the lost coin; the father longs for his son’s return. Thus, the sinner does not turn to God; God turns to the sinner.

So why is it that our efforts to seek God are frustrated? Why is it when we look for God we come up with “divine hiddenness” instead of divine presence? It goes back to that problem of orientation. We do not seek God in the power of our own strength, but by trusting in the power of His might. We look for Him as though He were somewhere else, when He has been with us all along. The poet Rumi put it like this: “If in thirst you drink water from a cup, you see God in it. Those who are not in love with god will only see their own faces in it.” We are to seek God in love and in trust, knowing that He is already there, seeking us.

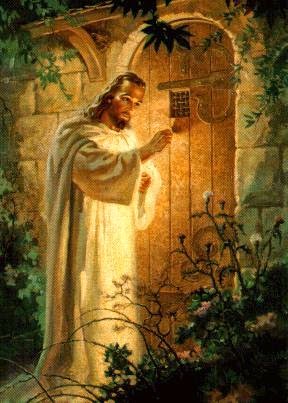

“Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and eat with him, and he with me.” (Rev 3:20)

The Almighty is standing at the door of your heart, knocking. Will you bid Him to enter?

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Thursday, May 8, 2014

The Resurrection of Hope Part II: Hope and Christianity

I have always been a big fan of the science fiction genre; whether its literature, film or even video games. I can trace this interest all the way back to childhood when I first saw the 1960 classic the Time Machine. Every time the main character would wind up that chair to travel through time, my eyes would just go wide with amazement. The idea of time travel is just fascinating. I think that’s always been part of the draw of science fiction; it makes us think of limitless possibilities and fills us with a sense of wonder and hope for the future.

One rainy afternoon a few years ago I sat down and read H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. A sense of anticipation came over me, and as I turned page after page, there was this distinct feeling of reconnecting with my childhood memories of the movie. It was one of those rare moments where you feel like a kid again. By the time I got to the end of the book, my eyes did go wide with amazement; amazement of an altogether different sort. I was shocked to find that the story was completely different than the movie. The traveler goes forward into the distant future to discover the destiny of man; but he doesn’t find alien races or technological marvels. He finds nothing. All that is left is a dead earth, save for a few lichens and moss, orbiting a gigantic red sun. The only sounds are the rush of the wind and the gentle ripple of the sea. “Beyond these lifeless sounds,” writes Wells, “the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over.” I put down the book in a stunned…silence. This was not at all what I had expected. The ending of the Time Machine reminds me a bit of the existential crisis of postmodern man. What do we have to look forward to at the end of our journey; with all our toiling, our passions, our struggles and our ambition? If the naturalist worldview is correct, not very much.

Last week I talked about the hope of humanism, demonstrating how the ‘New Atheists’ have substituted the pessimism of old with a more attractive, humanist Utopian idealism. But several atheist writers have emerged to attack and critique this ‘hope’ of the New Atheism. They accuse people like Dawkins of “going soft.” As one prominent atheist blogger put it, “We are Atheists. We believe that the Universe is a great uncaused, random accident. All life in the Universe past and future are the results of random chance acting on itself. While we acknowledge concepts like morality, politeness, civility seem to exist, we know they do not. Our highly evolved brains imagine that these things have a cause or a use, and they have in the past, they’ve allowed life to continue on this planet for a short blip of time. But make no mistake: all our dreams, loves, opinions, and desires are figments of our primordial imagination. They are fleeting electrical signals that fire across our synapses for a moment in time.” When put under the microscope; atheism cannot offer us hope. If we are simply the products of random time and chance in a blind and impersonal cosmos, then life ultimately has no objective, purpose or meaning. Just like the ending of the Time Machine, it is a deep silence and a profound nothingness that awaits us.

You see, under the naturalist worldview, we simply cannot get around the fact that everything ends in death. The great Emperor Marcus Aurelius once said “Alexander the Great and his stable boy were leveled in death.” How can there be any real hope in humanism if this is the case? All I can do is to try to escape from this inevitable reality. All I can do is to try to “authenticate myself” in any way possible.

But everything changes if God exists. The Christian view of God is important because it suggests that God is personal; He has revealed Himself to us in space and time; He has invaded human history with the Incarnation. The faceless now has a face; the unknowable has been made known. Thus God is not some blind watchmaker who sets the world in motion for no real purpose; rather He has created us to be in relationship with Himself. It is in this way that life suddenly has an objective meaning and purpose. You are not the product of random time and chance; rather you are the product of a loving God. You are not a momentary blip of being; rather you are a being of eternal significance. Your actions are not simply methods of escape or ways to “authenticate yourself”; rather what you do today matters eternally. Why must we debase ourselves with such naturalism? Why must we descend into despair and worthlessness when the Christian God says we are of infinite worth? My point here is that God has endowed us with reason above all other creation not so that we might despair of our condition; but so that our condition might cause us to seek Him. “Pain,” C.S. Lewis wrote, “is God’s megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”

I cannot escape the reality of suffering. The Buddha taught that life itself is suffering and the Christian would agree with that wisdom. We live in a broken and fallen world that is not operating as it was intended. I have likened it to a computer virus infecting the operating system. The computer still powers up; you can still run most of your programs; but it is erratic. It runs more slowly than it should. It shuts down unexpectedly. Every time you turn it on, you wonder how much longer it is going to last. But while the naturalist, the atheist or the humanist must somehow insert meaning into life when there is none; the Christian says there actually is meaning. We see the world for how it actually is, not as we wish it to be.

To the naturalist, no amount of “authenticating ourselves” can eclipse the fact that if we are merely the product of random causes, our suffering also has no meaning. Suffering is just another random event of which we are nothing more than helpless prisoners. Some might call it ‘fate,’ for rather than subjecting themselves to a benevolent God, naturalists have instead subjected themselves to a blind determinism. The grave is ever looming, and that is all there is.

By contrast, the Christian worldview says there is meaning even in the midst of our suffering. Even though there is a virus infecting our operating system, God uses it to bring about good. I can think of no better example of this than the story of Jacob. After all that happened to him, he was still able to confidently utter those famous words “You meant it for harm, but God meant it for good.” And as Christians we can claim that as a promise. Our trials can be used to bring about good.

You see, most people understand hope as a kind of wishful thinking. We want something to happen, so we hope for a certain outcome that may or may not work out. I hope the weather will be nice enough so I can take a walk today. I hope I get that promotion at work because I really need the money. But the Christian does not view hope in this way. The biblical definition of hope is “confident expectation.” Christian hope is the confidence that something will come to pass because God has promised us that it will.

But this hope is not Utopian. It does not say I will be healed of my every illness, it does not say God will make me healthy and wealthy, it does not say that all wars will be ended or that we will reach distant galaxies. Rather, it says “And lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.” It says that I am not alone; that the God who Himself became man and suffered as a man is with me, suffering with me as I suffer. This is what the Psalmist means when he says “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.” When I suffer, I am not cast adrift at sea without any sense of purpose or hope; rather, God is my refuge and in that refuge I am given the strength to get through the trial; not to try to “authenticate myself” around it.

According to the naturalistic worldview, suffering, sickness and death can have no meaning. But to the Christian, we believe that behind this broken world there is a sovereign God who will one day do a system restore to this faulty operating system and set it back to the original factory default. I can believe this because God has promised it and because He has demonstrated it in the resurrection of Jesus Christ. He is the pattern.

At the end of my previous blog on the resurrection, I asked the question “what if it were true?” If Jesus was indeed raised from the dead, then the great reversal has begun. Death itself has been defeated. To the atheist; death claims everything. But to the Christian; death is but a passing through a doorway from one method of being into another. You are not a random collection of atoms to be dissolved; you are ceaseless, eternal. As Christ was raised, we shall be raised, for He said: “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die; 26 and whoever lives by believing in me will never die. Do you believe this?” He gives us the promise, all we have to do is believe it, even if it is a struggle; then we too can live in the hope of confident expectation where death does not have the final word.

My hope is built on nothing less

Than Jesus Christ, my righteousness;

I dare not trust the sweetest frame,

But wholly lean on Jesus’ name.

On Christ, the solid Rock, I stand;

All other ground is sinking sand,

All other ground is sinking sand.

When darkness veils His lovely face,

I rest on His unchanging grace;

In every high and stormy gale,

My anchor holds within the veil.

His oath, His covenant, His blood,

Support me in the whelming flood;

When all around my soul gives way,

He then is all my hope and stay.

(My Hope is Built, 1834)

One rainy afternoon a few years ago I sat down and read H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. A sense of anticipation came over me, and as I turned page after page, there was this distinct feeling of reconnecting with my childhood memories of the movie. It was one of those rare moments where you feel like a kid again. By the time I got to the end of the book, my eyes did go wide with amazement; amazement of an altogether different sort. I was shocked to find that the story was completely different than the movie. The traveler goes forward into the distant future to discover the destiny of man; but he doesn’t find alien races or technological marvels. He finds nothing. All that is left is a dead earth, save for a few lichens and moss, orbiting a gigantic red sun. The only sounds are the rush of the wind and the gentle ripple of the sea. “Beyond these lifeless sounds,” writes Wells, “the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over.” I put down the book in a stunned…silence. This was not at all what I had expected. The ending of the Time Machine reminds me a bit of the existential crisis of postmodern man. What do we have to look forward to at the end of our journey; with all our toiling, our passions, our struggles and our ambition? If the naturalist worldview is correct, not very much.

Last week I talked about the hope of humanism, demonstrating how the ‘New Atheists’ have substituted the pessimism of old with a more attractive, humanist Utopian idealism. But several atheist writers have emerged to attack and critique this ‘hope’ of the New Atheism. They accuse people like Dawkins of “going soft.” As one prominent atheist blogger put it, “We are Atheists. We believe that the Universe is a great uncaused, random accident. All life in the Universe past and future are the results of random chance acting on itself. While we acknowledge concepts like morality, politeness, civility seem to exist, we know they do not. Our highly evolved brains imagine that these things have a cause or a use, and they have in the past, they’ve allowed life to continue on this planet for a short blip of time. But make no mistake: all our dreams, loves, opinions, and desires are figments of our primordial imagination. They are fleeting electrical signals that fire across our synapses for a moment in time.” When put under the microscope; atheism cannot offer us hope. If we are simply the products of random time and chance in a blind and impersonal cosmos, then life ultimately has no objective, purpose or meaning. Just like the ending of the Time Machine, it is a deep silence and a profound nothingness that awaits us.

You see, under the naturalist worldview, we simply cannot get around the fact that everything ends in death. The great Emperor Marcus Aurelius once said “Alexander the Great and his stable boy were leveled in death.” How can there be any real hope in humanism if this is the case? All I can do is to try to escape from this inevitable reality. All I can do is to try to “authenticate myself” in any way possible.

But everything changes if God exists. The Christian view of God is important because it suggests that God is personal; He has revealed Himself to us in space and time; He has invaded human history with the Incarnation. The faceless now has a face; the unknowable has been made known. Thus God is not some blind watchmaker who sets the world in motion for no real purpose; rather He has created us to be in relationship with Himself. It is in this way that life suddenly has an objective meaning and purpose. You are not the product of random time and chance; rather you are the product of a loving God. You are not a momentary blip of being; rather you are a being of eternal significance. Your actions are not simply methods of escape or ways to “authenticate yourself”; rather what you do today matters eternally. Why must we debase ourselves with such naturalism? Why must we descend into despair and worthlessness when the Christian God says we are of infinite worth? My point here is that God has endowed us with reason above all other creation not so that we might despair of our condition; but so that our condition might cause us to seek Him. “Pain,” C.S. Lewis wrote, “is God’s megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”

I cannot escape the reality of suffering. The Buddha taught that life itself is suffering and the Christian would agree with that wisdom. We live in a broken and fallen world that is not operating as it was intended. I have likened it to a computer virus infecting the operating system. The computer still powers up; you can still run most of your programs; but it is erratic. It runs more slowly than it should. It shuts down unexpectedly. Every time you turn it on, you wonder how much longer it is going to last. But while the naturalist, the atheist or the humanist must somehow insert meaning into life when there is none; the Christian says there actually is meaning. We see the world for how it actually is, not as we wish it to be.

To the naturalist, no amount of “authenticating ourselves” can eclipse the fact that if we are merely the product of random causes, our suffering also has no meaning. Suffering is just another random event of which we are nothing more than helpless prisoners. Some might call it ‘fate,’ for rather than subjecting themselves to a benevolent God, naturalists have instead subjected themselves to a blind determinism. The grave is ever looming, and that is all there is.

By contrast, the Christian worldview says there is meaning even in the midst of our suffering. Even though there is a virus infecting our operating system, God uses it to bring about good. I can think of no better example of this than the story of Jacob. After all that happened to him, he was still able to confidently utter those famous words “You meant it for harm, but God meant it for good.” And as Christians we can claim that as a promise. Our trials can be used to bring about good.

You see, most people understand hope as a kind of wishful thinking. We want something to happen, so we hope for a certain outcome that may or may not work out. I hope the weather will be nice enough so I can take a walk today. I hope I get that promotion at work because I really need the money. But the Christian does not view hope in this way. The biblical definition of hope is “confident expectation.” Christian hope is the confidence that something will come to pass because God has promised us that it will.

But this hope is not Utopian. It does not say I will be healed of my every illness, it does not say God will make me healthy and wealthy, it does not say that all wars will be ended or that we will reach distant galaxies. Rather, it says “And lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.” It says that I am not alone; that the God who Himself became man and suffered as a man is with me, suffering with me as I suffer. This is what the Psalmist means when he says “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.” When I suffer, I am not cast adrift at sea without any sense of purpose or hope; rather, God is my refuge and in that refuge I am given the strength to get through the trial; not to try to “authenticate myself” around it.

According to the naturalistic worldview, suffering, sickness and death can have no meaning. But to the Christian, we believe that behind this broken world there is a sovereign God who will one day do a system restore to this faulty operating system and set it back to the original factory default. I can believe this because God has promised it and because He has demonstrated it in the resurrection of Jesus Christ. He is the pattern.

At the end of my previous blog on the resurrection, I asked the question “what if it were true?” If Jesus was indeed raised from the dead, then the great reversal has begun. Death itself has been defeated. To the atheist; death claims everything. But to the Christian; death is but a passing through a doorway from one method of being into another. You are not a random collection of atoms to be dissolved; you are ceaseless, eternal. As Christ was raised, we shall be raised, for He said: “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die; 26 and whoever lives by believing in me will never die. Do you believe this?” He gives us the promise, all we have to do is believe it, even if it is a struggle; then we too can live in the hope of confident expectation where death does not have the final word.

My hope is built on nothing less

Than Jesus Christ, my righteousness;

I dare not trust the sweetest frame,

But wholly lean on Jesus’ name.

On Christ, the solid Rock, I stand;

All other ground is sinking sand,

All other ground is sinking sand.

When darkness veils His lovely face,

I rest on His unchanging grace;

In every high and stormy gale,

My anchor holds within the veil.

His oath, His covenant, His blood,

Support me in the whelming flood;

When all around my soul gives way,

He then is all my hope and stay.

(My Hope is Built, 1834)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)